NAND Flash Memory Analysis and Decoding - Unveiling ECC Scattering in Unknown Devices

on

Exploring NAND Memories

When in possession of a device whose internals one wishes to understand, accessing the content of the flash memory is not always straightforward. Due to the nature of NAND memories, an error correction algorithm is applied to all content, which can cause unintentional obfuscation of the content. Some manufacturers of processors that directly control NAND-type memories or developers of “protected” software choose to customize the way these algorithms function.

In this article, we will explore the basic structure of flash memory, why error correction exists, and how to identify the scattering of the error correction algorithm used.

Flash Memories

Flash memories have emerged as the backbone of digital storage in the contemporary era. Found in devices as varied as SSDs, USB drives, and SD cards, these memories bring an irresistible combination of speed, durability, and the ability to retain data even in the absence of power.

Historically, before the rise of flash memories, the main storage devices were based on magnetic media, such as hard disks and floppy disks, or on EPROMs (Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory). While magnetic media had moving parts and were more prone to physical failures, EPROMs required a specific erasure process, making the rewriting of data a slower and less efficient process.

Within the category of flash memories, we find different variations, with NOR and NAND versions being the most predominant. In this article, we will focus on NAND flash memories, recognized for their high storage density and widely used in everyday storage devices, ensuring speed and reliability in reading and writing data.

Anatomy of a NAND Cell

Detailed diagram of a NAND cell

At the heart of flash memory technology lies the intricate architecture of a NAND cell. The illustration above outlines the fundamental components of the cell: the Control Gate, the Floating Gate, insulating oxide layers, along with N-Type Source and N-Type Drain terminals, all built on a P-type substrate. Bits are stored in the flash memory by retaining electrons in the Floating Gate.

During the write operation, a voltage is imposed on the Control Gate, inducing electrons to cross the oxide barrier and lodge in the Floating Gate. Once the electrons reach the Floating Gate, they remain there, denoting a “written” state.

To read the stored information, a voltage is applied to the Control Gate. If there are electrons in the Floating Gate, they will create a repulsive force, blocking the flow of electrons from the Source to the Drain. This state is recognized as a “0” bit. However, if the Floating Gate is unoccupied, the electric current will flow unimpeded, corresponding to a “1” bit.

NAND cell in the “written” state

Finally, the electronic configuration — whether its absence or presence — determines whether the cell is representing a “0” or “1” bit. The subsequent image shows a cell in the “erased” state, characterized by the free flow of electrons between the terminals.

NAND cell in the “erased” state

NAND Memory Architecture

Diagram representing the organization of a NAND block

NAND memory is meticulously organized in a hierarchical structure. Starting with the smallest unit, we have the cell. These cells are grouped to form pages. Moving up the hierarchy, multiple pages are then consolidated to constitute a block, as illustrated in the diagram above.

This structural arrangement is not just for organization. It plays a vital role in the efficiency of flash memory operations. An important detail to consider is that, in various devices based on flash technology, the erase operation is performed at the block level, and not on individual cells or pages.

The image exemplifies a NAND memory containing pages of 2048 bytes of data added with 64 bytes designated for error correction, totaling 2112 bytes per page. These pages are grouped into blocks that house 64 pages each, resulting in 128K bytes of data and 4K bytes for correction.

The additional bytes in each page are not mere supplements. They are intrinsic to the memory’s integrity. Although stored in the same way as any other byte, they are often allocated for specific functions, such as parity in Error Correction (ECC) algorithms. This correction is indispensable, as during manufacturing or even over use, some cells of the NAND memory may present defects or wear out, compromising the accuracy of stored data. Therefore, ECC acts as a protective layer, ensuring the reliability of data even in the presence of imperfections in the memory.

Reading Flash Memories

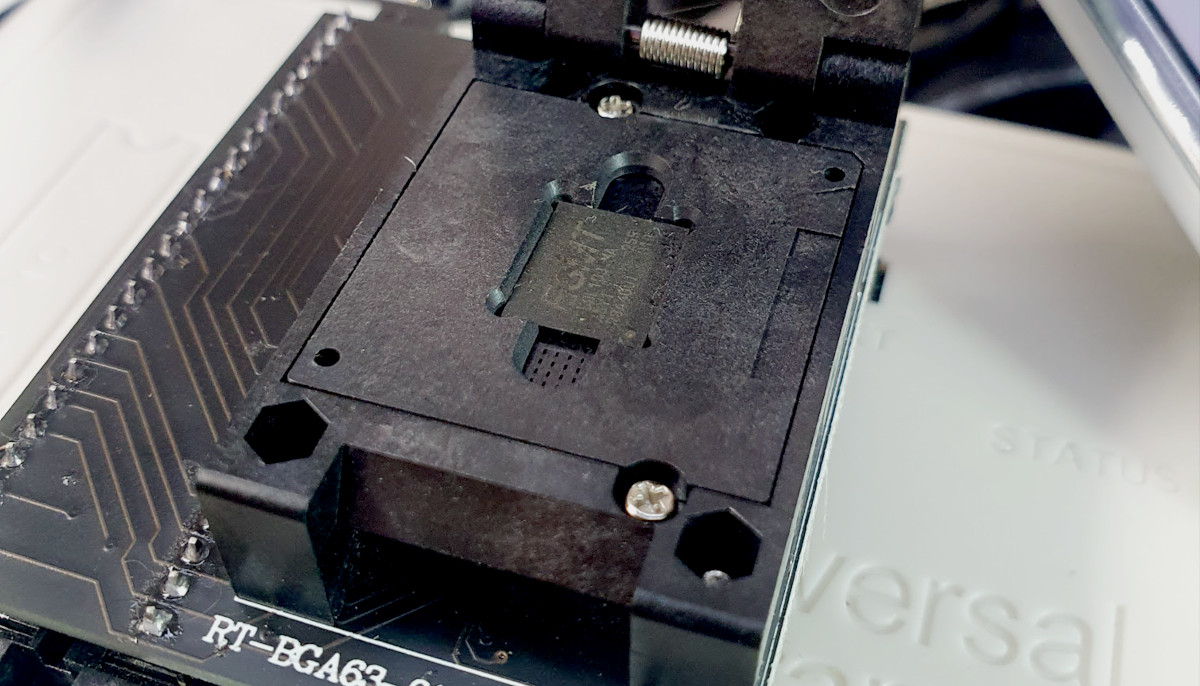

When dealing with reading and writing in Flash memories, a variety of devices are available. For flash memories with less conventional encapsulations, like BGA (Ball Grid Array), I often turn to the RT809H programmer, using a specific adapter for such encapsulation. The flash memory in question was originally extracted from a device by PAX, a model available on Mercado Livre under the description “card machine”. It is worth mentioning that the encapsulation type of this flash memory is BGA63, indicating an arrangement of 63 pins in the ball-grid-array format.

Flash Memory in the universal programmer RT809H ready for reading

Flash Memory in the universal programmer RT809H ready for reading

After extracting the data from the flash memory, a crucial step is using the binwalk tool. This command functions to scan and list possible signatures of known files contained in the memory dump, allowing a preliminary analysis of its content. This stage is essential to discern if we will face challenges when trying to decipher the stored data, such as if they are encrypted.

It is important to note that the image produced by the RT809H programmer depicts the content of the flash memory in its purest state, without any filtering. This means that the ECC (Error-Correcting Code) parity bits are included. This feature can introduce nuances during the analysis, as not all signatures will be accurately recognized, especially considering files that may start at the end of a memory page.

$ binwalk F59L1G81MA@BGA63_1111.BIN

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

438548 0x6B114 Base64 standard index table

(...)

3514378 0x35A00A PC bitmap, Windows 3.x format,, 320 x 240 x 24

7839754 0x77A00A uImage header, header size: 64 bytes, header CRC: 0x538F3DE9, created: 2021-05-27 08:14:51, image size: 3696472 bytes, Data Address: 0x80800000, Entry Point: 0x80800000, data CRC: 0xA22F74A5, OS: Linux, CPU: ARM, image type: OS Kernel Image, compression type: none, image name: "Linux-2.7.93.9707R"

7839818 0x77A04A Linux kernel ARM boot executable zImage (little-endian)

7857081 0x77E3B9 gzip compressed data, maximum compression, from Unix, last modified: 1970-01-01 00:00:00 (null date)

(...)

20815882 0x13DA00A uImage header, header size: 64 bytes, header CRC: 0xF95F6882, created: 2021-05-27 08:20:25, image size: 8185419 bytes, Data Address: 0x83800000, Entry Point: 0x83800000, data CRC: 0xE5674944, OS: Linux, CPU: ARM, image type: RAMDisk Image, compression type: none, image name: "RAMDISK-2.7.93.9707R"

(...)

20815946 0x13DA04A gzip compressed data, maximum compression, from Unix, last modified: 2021-05-27 08:20:23

33792010 0x203A00A uImage header, header size: 64 bytes, header CRC: 0x588DFFBC, created: 2021-05-27 08:19:13, image size: 6412038 bytes, Data Address: 0x0, Entry Point: 0x0, data CRC: 0x32979F1E, OS: Linux, CPU: ARM, image type: Firmware Image, compression type: none, image name: "BASE-2.7.93.9707R"

33792074 0x203A04A gzip compressed data, maximum compression, from Unix, last modified: 2021-05-27 08:19:11

46768138 0x2C9A00A UBI erase count header, version: 1, EC: 0x3, VID header offset: 0x800, data offset: 0x1000

Entropy assessment is an effective technique to detect encrypted or compressed content in a memory. When we talk about entropy in data, we are referring to the amount of information or unpredictability contained in these data. The binwalk tool offers a specific mode for measuring this entropy.

Files that are compressed or encrypted tend to display an apparently random data pattern, resulting in an entropy measure that approaches 1. In contrast, “plain-text” files or unencoded data generally have significantly lower entropy, tending towards values closer to 0, as their content is more predictable.

To explore this functionality in binwalk, use the -E option, which activates the entropy measurement mode. When executed, you will receive a graph that visually represents the entropy variations throughout the file, facilitating the identification of encrypted or compressed segments.

$ binwalk -E F59L1G81MA@BGA63_1111.BIN

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL ENTROPY

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

0 0x0 Falling entropy edge (0.027839)

7880704 0x784000 Rising entropy edge (0.995063)

12345344 0xBC6000 Falling entropy edge (0.000000)

20869120 0x13E7000 Rising entropy edge (0.997811)

29257728 0x1BE7000 Falling entropy edge (0.000000)

33824768 0x2042000 Rising entropy edge (0.999076)

40386560 0x2684000 Falling entropy edge (0.372003)

47253504 0x2D10800 Falling entropy edge (0.725862)

62879744 0x3BF7800 Falling entropy edge (0.737729)

67244032 0x4021000 Rising entropy edge (0.966013)

67311616 0x4031800 Falling entropy edge (0.776734)

69611520 0x4263000 Falling entropy edge (0.790624)

69679104 0x4273800 Rising entropy edge (0.972091)

69814272 0x4294800 Falling entropy edge (0.836573)

70322176 0x4310800 Falling entropy edge (0.844177)

72689664 0x4552800 Falling entropy edge (0.643195)

74008576 0x4694800 Falling entropy edge (0.783870)

74584064 0x4721000 Falling entropy edge (0.471472)

75259904 0x47C6000 Falling entropy edge (0.787818)

76613632 0x4910800 Falling entropy edge (0.823394)

76748800 0x4931800 Falling entropy edge (0.687502)

82837504 0x4F00000 Falling entropy edge (0.360502)

84291584 0x5063000 Falling entropy edge (0.775172)

84934656 0x5100000 Falling entropy edge (0.714603)

95385600 0x5AF7800 Falling entropy edge (0.788762)

103233536 0x6273800 Falling entropy edge (0.775540)

104992768 0x6421000 Falling entropy edge (0.750242)

124475392 0x76B5800 Falling entropy edge (0.281623)

125253632 0x7773800 Falling entropy edge (0.750710)

133507072 0x7F52800 Falling entropy edge (0.798972)

137566208 0x8331800 Falling entropy edge (0.768062)

137701376 0x8352800 Falling entropy edge (0.743758)

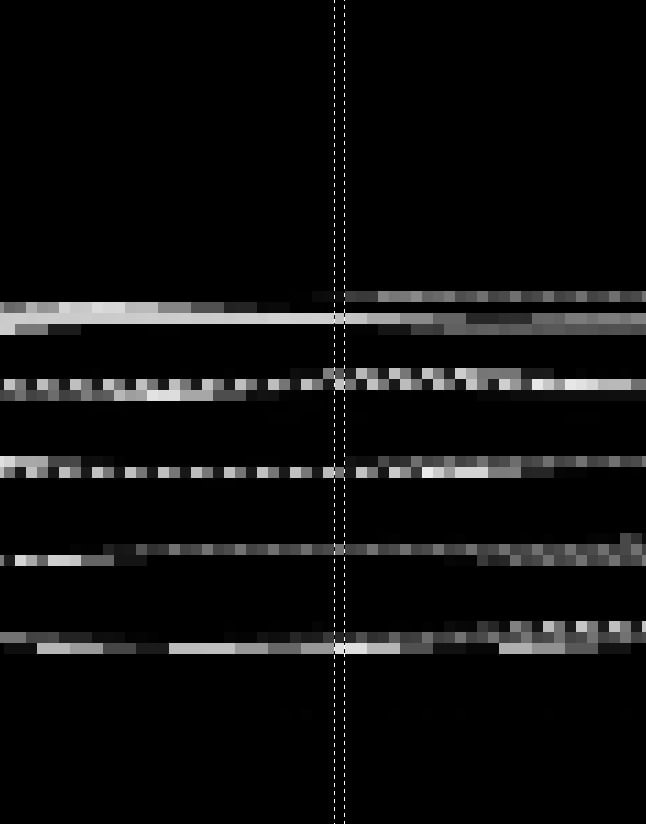

Entropy of the Read Image

In the presented entropy graph, the areas of high entropy stand out as peaks that approach the value of 1 on the vertical axis. These regions point to sections of data that have a distribution of bits that appears random, which is typical of compressed or encrypted data.

By correlating the position of these peaks with the information provided by the binwalk command, we can understand the nature of these high entropy segments. In our case, the points of high entropy correspond to compressed parts, and not encrypted data. This deduction becomes clear when we see that binwalk identified signatures related to data compressed with gzip at the indicated positions.

The fact of recognizing these signatures clearly shows that the content, although compressed, is not encrypted. If it were, binwalk would not have identified these signatures, as encrypted data looks like a bunch of random information, without specific patterns. Thus, looking at both the entropy graph and the information from binwalk, we get a good idea of the structure and type of data in the analyzed flash memory.

When ECC Scattering is Not Standard

To ensure that data is accessed accurately, it is crucial to exclude the parity bits inserted into each memory page. Assuming that the last 64 bytes of each page are allocated for ECC, we can create a Python script that reads the 2112 bytes (representing the full memory page) and writes only the 2048 bytes corresponding to the pure data, disregarding the ECC, into a new file.

#!/usr/bin/env python

f = open("F59L1G81MA@BGA63_1111.BIN", "rb")

o = open("FIXEDDATA.bin", "wb")

pagesToRead = 65536

for i in range(pagesToRead):

page = f.read(2112)

data = bytearray(page[:2048]) # Nuke ECC

o.write(data)

f.close()

o.close()

With the data now cleaned, the next step is to identify the files present to verify the efficacy of our assumption. A quick look at the list of files highlighted by binwalk will give us an indication.

$ binwalk F59L1G81MA@BGA63_1111.BIN

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

438548 0x6B114 Base64 standard index table

439650 0x6B562 DES PC1 table

439738 0x6B5BA DES PC2 table

440945 0x6BA71 DES SP2, little endian

441738 0x6BD8A DES SP1, little endian

477666 0x749E2 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header (...)

478540 0x74D4C Object signature in DER format (PKCS header (...)

479065 0x74F59 Object signature in DER format (PKCS header (...)

1384724 0x152114 Base64 standard index table

1385826 0x152562 DES PC1 table

1385914 0x1525BA DES PC2 table

1387121 0x152A71 DES SP2, little endian

1387914 0x152D8A DES SP1, little endian

1423842 0x15B9E2 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header (...)

1424716 0x15BD4C Object signature in DER format (PKCS header (...)

1425241 0x15BF59 Object signature in DER format (PKCS header (...)

3514378 0x35A00A PC bitmap, Windows 3.x format,, 320 x 240 x 24

7839754 0x77A00A uImage header, header size: 64 bytes, header (...)

7839818 0x77A04A Linux kernel ARM boot executable zImage (litt(...)

7857081 0x77E3B9 gzip compressed data, maximum compression, (...)

(...)

We can identify a bitmap right at the beginning of the image, where binwalk is even able to identify its size and bit depth:

3514378 0x35A00A PC bitmap, Windows 3.x format,, 320 x 240 x 24

A distinctive characteristic of bitmaps is the way they store color information. The bytes in the file map directly to the colors of the image. Thus, when we have a region of the image that displays a single color, that color is represented by consecutive sequences of identical bytes in the file. This property is especially useful when we try to discern the distribution of error-correcting bits (ECC). If a segment of the bitmap, fitting to a memory page, displays the same color as another segment on a different page, it’s expected that their corresponding ECC bits would be identical.

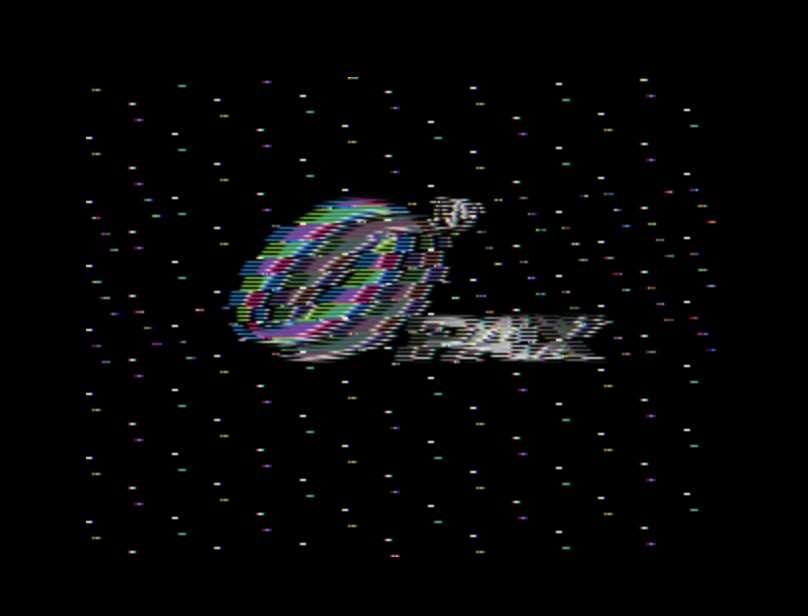

Considering that the identified image has a color depth of 24 bpp (bits per pixel), each pixel is represented by 3 bytes. Given a memory page capacity of 2048 bytes, this translates to about 682 pixels per page. This is slightly more than two lines of the image. The attempt to access the bitmap in its current form suggests inconsistencies, leading us to question our initial assumptions about the distribution of ECC bits.

Corrupted PAX Logo

Corrupted PAX Logo

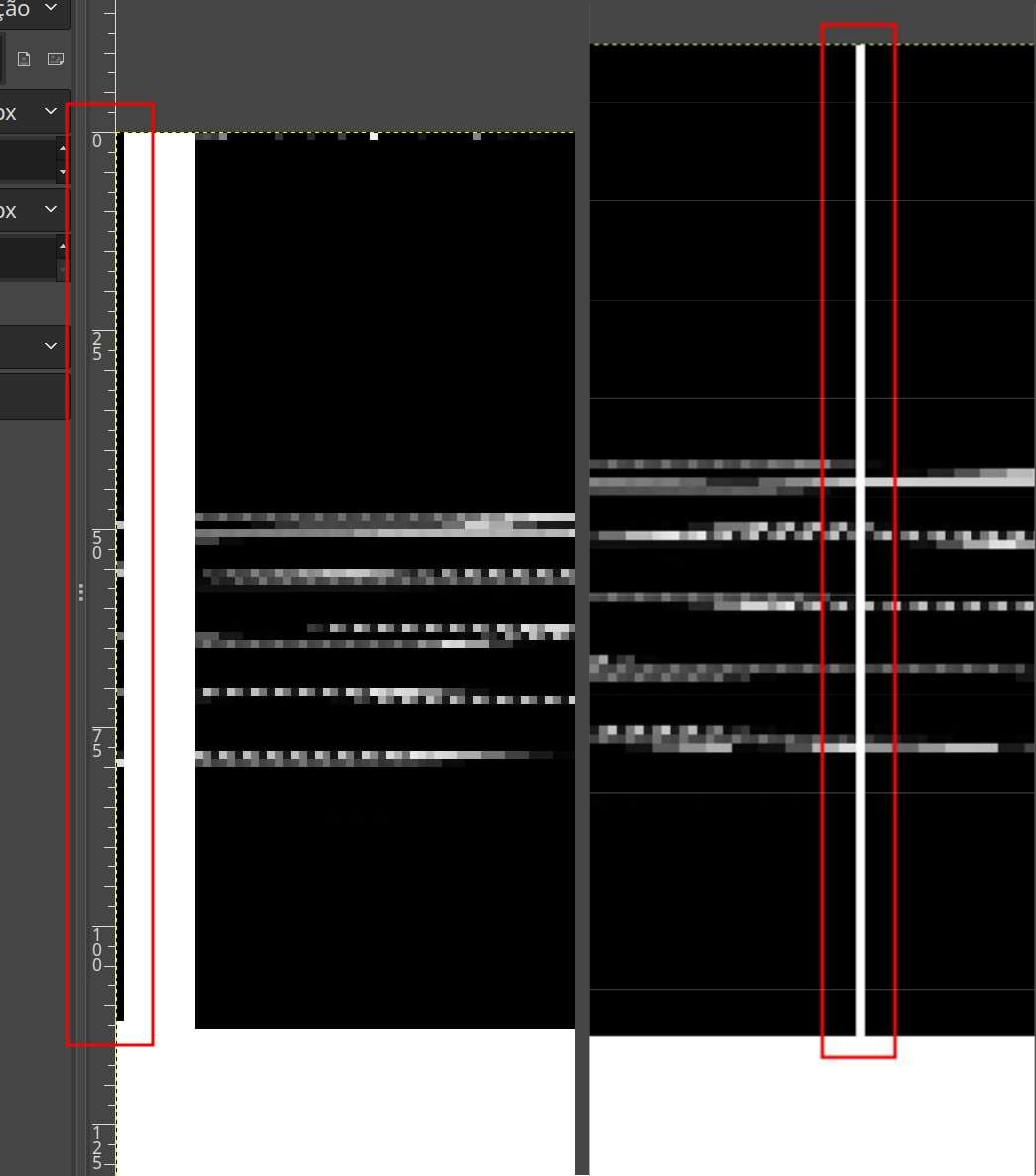

For proper interpretation, it’s vital to extract multiple pages from the memory containing the bitmap data in an aligned manner. This way, we can ensure that at every 2112 byte interval, we are dealing with a new page, not a continuation of the previous one. Subsequently, we can use an image editing software that allows manipulating images in arbitrary “RAW” formats. In this context, we will use GIMP to analyze the raw image data. One of the advantages of GIMP is the flexibility in defining the image geometry and pixel formatting.

To facilitate the identification of ECC bits, we’ll set the image width to 2112, corresponding to the memory page size. This will allow us to visualize each memory page as a distinct line. We’ll choose an 8-bit per pixel representation in monochrome to ensure an exact correspondence of 2112 bytes per line. Regarding the height, we’ll opt for at least 100 lines to provide a clear view of variations between different memory pages.

Examining the visual representation provided by GIMP, we notice clearly defined segments of 512 bytes within each memory page. These segments are interspersed with thinner columns, whose appearance seems directly influenced by the adjacent block.

512 byte blocks

512 byte blocks

Looking closer, we realize that the completely black lines display a column with consistent patterns to the left of the 512-byte mark. Contrary to this, lines that show some variation also manifest discrepancies in that same column on the left. Based on this observation, we can infer that the columns positioned both to the left and right of the 512-byte segment represent parity data, and are not an intrinsic part of the bitmap. This becomes even more evident considering that the first lines of the bitmap are entirely black.

Considering the memory page as a whole, another detail stands out: despite the observed pattern, there is a completely white column in an unexpected position. Additionally, the first column, which theoretically should be white, appears to be displaced or altered in some way.

Column apparently switched place

Column apparently switched place

The hypothesis suggests that, for some reason, these columns may have been switched during the scattering process. To validate this assumption, a practical approach would be to use GIMP itself to reposition the column and assess if the resulting content aligns harmoniously with the rest of the memory page.

Switching identified columns

Switching identified columns

The above image validates our conjecture, highlighting that the reallocation of columns provides a more coherent visualization of the content. Although it seems unusual at first glance, considering the security nature of the device, it is plausible to think that this altered arrangement could be a deliberate way of hiding data. This peculiarity is not mentioned in any public documentation available for the device’s processor.

Based on these findings, we have the tools needed to refine our Python script, aiming to eliminate the parity bits and rearrange the 512-byte segments, in order to obtain a refined and coherent image.

#!/usr/bin/env python

f = open("F59L1G81MA@BGA63_1111.BIN", "rb")

o = open("FIXEDDATA.bin", "wb")

pagesToRead = 65536

for i in range(pagesToRead):

page = f.read(2112)

data = bytearray(page[10:10+512] + page[535:535+512] + page[1060:1060+512] + page[1585:1585+512])

data[len(data)-48-1] = page[0]

o.write(data)

f.close()

o.close()

After all the steps of analysis and correction, we successfully extracted the bitmap and validated that all our hypotheses and methods of analysis were correct:

Adjusted PAX Logo

Adjusted PAX Logo

Conclusion

It is essential to highlight that our approach was limited to removing the parity bits, without actually applying the error correction algorithm. As mentioned earlier, flash memories, particularly NAND type, can have defective bits, even from the time of manufacturing. Omitting the specific ECC algorithm may result in inconsistencies in the final data.

Fortunately, the content of this specific device was not encrypted, which made it easier for us in the analysis of scattering, taking advantage only of known content. If the content had been encrypted, it would be essential to identify a recurring pattern (such as empty memory pages) where the ECC information would be recorded.